IEEFA: Three reasons the U.S. LNG pause does not threaten South Korea’s energy security and transition

IEEFA [Michelle (Chaewon) Kim]—Since the U.S. Biden Administration announced the temporary pause on new liquefied natural gas (LNG) export approvals early this year, many Asian countries have expressed concerns about the potential disruption in energy security and decarbonization goals.

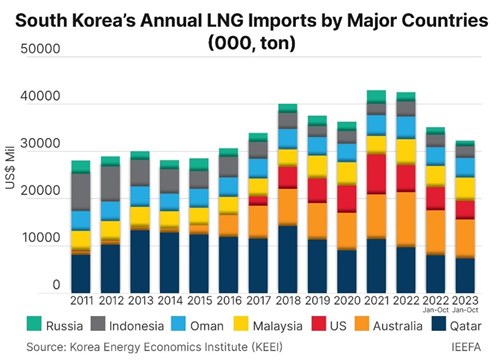

South Korea, the largest U.S. LNG importer in Asia until 2022, is one of them. SK gas and KOSPO were identified as potential buyers for new LNG projects that could be affected. However, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) determined the U.S. LNG export pause does not threaten South Korea’s energy security and transition goals for the following three reasons.

U.S. LNG imports have largely been prompted by geopolitical reasons. South Korea began importing U.S. LNG in 2017, driven more by political motives than by concerns for energy security.

Despite the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in 2012 and the U.S. Obama Administration labeling LNG as a “bridge fuel” in 2014 to promote the role of U.S. LNG in global energy security, there was no significant discussion of U.S. LNG as a major energy source in South Korea until 2017. That year, South Korea’s U.S. LNG intake spiked 70 times year-on-year after the first U.S. LNG export project, Sabine Pass, started in 2016 and South Korea’s state-run gas utility, KOGAS, signed a long-term contract with them.

There were other stronger reasons behind the U.S. LNG imports, such as trade disputes. During the U.S. Trump Administration in 2017, the mounting trade deficit caused by the Korea-U.S. FTA was addressed. LNG has been frequently mentioned as one of the potential remedies to mitigate this arguable deficit and alleviate potential risks of FTA cancellation by the U.S.

At the 2017 G20 Summit, South Korea’s Moon Administration declared the “Coal and Nuclear-free Economy” policy, supporting the narrative that LNG is a “green energy” in the energy transition pathway. In December 2017, the country’s Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy increased the targeted share of LNG in the power mix from 16.9% in 2017 to 18.8% in 2030.

In 2017, U.S. LNG imports by South Korea more than doubled year-on-year, coinciding with the start of the Korea-U.S. FTA renegotiation. In December 2020, the targeted share of LNG in South Korea’s power mix by 2030 further rose to 23.3% and U.S. LNG imports hit a historic high in 2021.

U.S. LNG showcased insecurity, unreliability and unaffordability. The belief that U.S. LNG will bolster South Korea’s energy security with abundant supply and affordable price has been questioned since the outages at the U.S. Freeport LNG export facility in 2022, which lasted more than a year.

In 2022, South Korea's U.S. LNG imports plummeted by 31.84% year-on-year due to the outage at the U.S. Freeport facility, which accounts for 17% of total U.S. LNG export capacity. Despite the promotion of U.S. LNG as a “savior” to stabilize global energy security, U.S. LNG showcased insecurity and unreliability when South Korea required a stable supply in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine war.

The disrupted supply of U.S. LNG reduced the power output from one of South Korea’s fleet of LNG-fired power plants. For example, SK E&S—an offtaker from the U.S. Freeport LNG export facility—lowered the operating rates of its LNG-fired power plants from 79% in 2021 to 71% in 2022 due to a lack of LNG supply.

This prompted the company and KOGAS to purchase more expensive spot LNG to make up for the losses due to the outages. The U.S. LNG cargoes purchased by South Korea were also costly, as prices were 16% higher than cargoes sold to neighboring Japan in 2022.

LNG’s role in the energy transition is diminishing. Despite less carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, LNG's role in greenhouse gas reduction is controversial due to its high methane emissions, as methane has a more significant warming effect than CO2 over a relatively short time frame. The South Korean government aims to decrease LNG's share in the power mix from 26.82% in 2023 to 9.3% by 2036.

South Korea’s LNG imports have already decreased by 4.9% in 2023 amid increased nuclear and renewable energy generation. This trend is likely to continue with the country’s strengthened decarbonization targets.

The predicted annual reduction rate of LNG demand in South Korea (3.6%) could offset the portion of U.S. LNG in total LNG imports, currently at 11%, by the end of this decade. It is also essential to recognize LNG as a fossil fuel that must be phased out by 2050. Prolonging its use by increasing U.S. LNG exports should not be justified for energy security or energy transition rhetoric.

The real energy security and transition for South Korea is reducing heavy reliance on imported fossil fuel and rapidly shifting to domestically produced renewable energy, as the country promised at the recent COP28.

Michelle (Chaewon) Kim is an Energy Finance Specialist, South Korea, at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

Related News

Related News

- Woodfibre LNG receives BCEAO order to move floatel to site to house non-local workforce

- QatarEnergy, Exxon seek to remove contractor from Texas gas project

- Veolia, Waga Energy and ENGIE collaborate to develop renewable natural gas industry in France

- Congo Brazzaville becomes an LNG exporting country

- Fulcrum LNG to pair with McDermott, Baker Hughes for Guyana gas project

- EU approves law to hit gas imports with methane emissions limit

- Veolia, Waga Energy and ENGIE collaborate to develop renewable natural gas industry in France

- Hawai'i Gas selects Eurus Energy America, Bana Pacific for hydrogen and renewable natural gas projects

- TotalEnergies increases LNG deliveries to Asia with two new contracts

- Desert Mountain Energy Corp. initiates helium production

Comments