Small-scale LNG applications make progress

I. LEWIS, contributing editor

Royal Dutch Shell has been keen to establish itself as a heavy investor in innovation over recent years, pioneering large-scale gas-to-liquids (GTL) facilities and floating liquefied natural gas (FLNG) production. Now, the company is promoting the potential of small-scale, modular LNG plants in tandem with its push to promote LNG as a cheaper and cleaner alternative to diesel as a transport fuel, especially in the North American market, where natural gas is abundant.

Shell's modular LNG push.

Employing what Shell calls a moveable modular liquefaction system (MMLS), these units are preassembled at the manufacturing plant and can be bolted together rapidly, either individually or in clusters. Potentially, they could be moved from one site to another as required. In other words, they are designed to bring flexibility to a sector more used to the challenging economics and long lead times of LNG mega-projects. Shell claims it could take less than two years from final investment decision for the first MMLS units to go into operation, and even less time for future orders.

Maarten Wetselaar, executive vice president for upstream international integrated gas at Shell, describes this as the “nano” approach to LNG plants. Mr. Wetselaar told journalists visiting the company’s technology center in Amsterdam earlier this year that the mobile, 0.25-million-ton-per-year (MMtpy) plants developed by Shell’s projects and technology business are competitive enough to match the economics of larger plants.

Shell and its partner, Kinder Morgan, plan to use 10 of these MMLS units together for a proposed LNG export project at El Paso Pipeline Partners’ Elba Island terminal near Savannah, Georgia, rather than building one 2.5-MMtpy train (Fig. 1). According to Mr. Wetselaar, this plan indicates just how competitive MMLS technology could be in the right circumstances, although Shell has not revealed any financial details.

|

|

Fig. 1. Illustration of proposed small-scale modular LNG capacity |

Shell hopes the speed with which the MMLS units can be put together and then integrated with the existing Elba Island terminal, originally designed for LNG imports, will prove the benefits of the modular approach. An MMLS unit is around the same size as a cargo train car, making it easier to manufacture and install, according to Shell.

The units include a simple inlet separation facility, an amine system, a dehydration unit, trace contamination removal equipment, a cold box, a cold separator and demethanizer, refrigerant compressors, LNG storage and a flare system. Other elements, including acid removal, liquefied petroleum gas fractionation and inlet compression, can be added as necessary. According to the company, the basic design can handle roughly 80% of global gas compositions and accept a range of feedstocks, including coalbed methane and rich associated gas.

El Paso Pipeline Partners has already been granted approval from the US Department of Energy (DOE) to export up to 4 MMtpy of LNG to countries with which the US has a Free Trade Agreement (FTA), and has applied for a license to export to non-FTA countries.

If the companies decide to move forward with the project, construction of the 1.5-MMtpy first phase should commence in late 2014, with LNG production targeted for 2016—a faster turnaround than could be expected with a larger, single LNG train. The 1-MMtpy second phase could also be up and running in 2016, if the extra regulatory approvals required are granted.

Given that around 20 companies have applied to the US DOE for LNG export permits, the speed of assembly of this modular technology could help give Elba Island an advantage in a highly competitive race to secure market share and generate income quickly.

Feeding LNG fuel networks.

Putting 10 MMLS units together on Elba Island may be an eye-catching move, but the technology may prove to be most valuable at a smaller scale, using individual, 2.5-MMtpy units to produce LNG from limited local gas reserves or for local usage. Shell believes the technology is best used for gas fields with flowrates of 15 million standard cubic feet per day (MMscfd)–40 MMscfd, where the total gas volume is less than 0.5 trillion cubic feet; or to produce from appraisal gas that would otherwise be flared.

Shell hopes to tie its MMLS together with its drive to promote LNG as a transport fuel, by making LNG feedstock for refueling networks more widely available. LNG is a cheaper, cleaner fuel than diesel for heavy-duty freight operations on both road and water, according to the company.

When burned as fuel, LNG reduces emissions that are increasingly heavily regulated around the world. It produces virtually no sulfur dioxide (SOx) and less nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter and greenhouse gases than diesel and marine fuels, which require expensive processing to reduce emissions. LNG fuel also makes engines run more quietly, which could be useful if their lower noise levels allow delivery trucks to operate at night in urban areas where noise limits are in force.

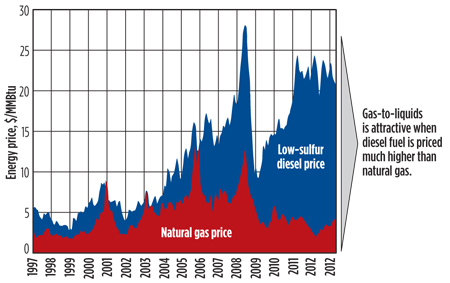

While putting a heavy-duty LNG-powered truck on the road might cost $40,000 to $75,000 more than a diesel-powered equivalent costing around $100,000, that difference could be recouped within three years without subsidies, according to an IHS CERA report on the sector published in mid-2012.1 The consultancy noted that the retail price of LNG was as low as $1.70 for the equivalent of a gallon of diesel, compared to a diesel price that was expected to average over $3.90/gallon over the following five years.

However, as with all new transport fuels, the major challenge is to develop refueling infrastructure in the first place, as no trucking company will switch to an LNG-powered fleet unless enough filling stations are in place. To that end, Shell has announced plans to build two standalone MMLS units in the US and one in Canada to supply LNG fuel for transport networks. It is also taking advantage of its own existing networks of refueling stations and has signed agreements with various fuel distributors to ensure widespread availability on major trucking routes.

A corridor of LNG fueling stations is under construction in Alberta, Canada to provide LNG to heavy-duty truck fleet customers using Shell truck stops along the 1,600-kilometer (km) route from Alberta to Canada’s Pacific coast. An MMLS facility is being built approximately 30 km west of Calgary, fed by gas from Shell’s Jumping Pound gas field complex. Shell hopes to produce first LNG in 2014.

In the US, Shell plans to build an MMLS unit at its Geismar chemical plant in Louisiana to supply LNG for use in marine and trucking applications and in oil and gas production. The unit might also supply LNG to trains along the Mississippi River, the Intracoastal Waterway, the offshore Gulf of Mexico and onshore hydrocarbon exploration areas of Texas and Louisiana.

Meanwhile, in the Great Lakes region, the company plans to install an MMLS unit at its facility in Sarnia, Ontario to supply LNG fuel to the Great Lakes region, the bordering US states and Canadian provinces and the St. Lawrence Seaway. Both LNG facilities are expected to begin operations in 2016, if regulatory approvals are granted.

European potential. Shell is also pushing LNG as a transport fuel in Europe. In this region, natural gas prices are higher than in the US, affecting LNG’s competitiveness as a transport fuel; however, emissions legislation is becoming stricter. In Norway, much of the shipping fleet plying the fjords around the coast already runs on LNG.

The company has chartered two LNG-fueled barges to operate on the River Rhine. These are the first completely LNG-fueled vessels to operate on inland waterways. The first, Greenstream, was launched in March (Fig. 2). Shell has also agreed to buy Norwegian LNG supplier Gasnor and is working with the Gate LNG terminal in Rotterdam to boost its access to marine customers.

|

|

Fig. 2. The Greenstream barge on the River Rhine is the first vessel |

Shell hopes to persuade these customers to adopt cleaner LNG as fuel ahead of the introduction of tighter EU sulfur regulations in 2015. Under these regulations, vessels operating in emissions control areas in the Baltic Sea, the English Channel and the North Sea must cut sulfur content to 0.1%, compared with 1% at present. In other EU waters, sulfur content will be limited to 0.5% by 2020. Similar restrictions apply for inland waterways.

“The proposition is quite simple,” Mr. Wetselaar explained. “If you are the owner of a barge that goes up and down the Rhine, you can actually replace the fuel oil you buy with LNG for a cheaper price and be 20 years ahead of environmental regulations that are getting tighter and tighter.”

Downstream base. Shell hopes to take advantage of its large downstream customer base in key markets, such as the US and Europe, to market LNG successfully as a transport fuel, persuading existing customers to switch (Fig. 3).

|

|

Fig. 3. Shell’s vision for integrating modular LNG into its operations. |

“The fact that we are able to build very small LNG plants at competitive unit rates is one thing,” Mr. Wetselaar said, “but we [also] have very deep portfolios of customers from shipping and heavy road transport that will currently buy diesel or heavy fuel oil from us and are quite willing to discuss buying LNG from us. If we didn't have the downstream business, it would be much more difficult to turn our energy into transport solutions.”

The company’s ability to translate this confidence into solid results will dictate how widespread the MMLS units will become. GP

Literature cited

1Groode, T. and R. McDonald, “The price of inequality: US long-haul trucking looks to LNG as a cheaper alternative to diesel,” IHS CERA, June 18, 2012.

Ian Lewisis the contributing editor for Europe, Africa and

the Middle East for Gas Processing. He is a writer on global energy, business and emerging markets. Having started his career as a correspondent for Reuters in London, Mr. Lewis then worked as a journalist in the Middle East and Spain before returning to the UK, where he now writes for various publications.

Comments